Warsaw, Poland

April 3rd 2012

You hear this song? It is about a worker who is happy to be getting up at 4AM to work in a steel mill in the socialist paradise of post war Poland.

At this the guide turns up the volume on the car stereo; the track is part 1940s American big band and part Polish Mazurka. I am the passenger in a vintage Soviet car driving through the streets of Warsaw on an excursion—Warsaw Behind the Scenes—that is a mix of conventional city tour and pub crawl. The next track gets more interesting—an officially sanctioned pop song of the mid-60s that sounds somewhere between The Beatles and The Carpenters—the chorus for which, my guide says, is Somebody loves me; the next is weirder still—1970s Funk with an east European flair.

At this the guide turns up the volume on the car stereo; the track is part 1940s American big band and part Polish Mazurka. I am the passenger in a vintage Soviet car driving through the streets of Warsaw on an excursion—Warsaw Behind the Scenes—that is a mix of conventional city tour and pub crawl. The next track gets more interesting—an officially sanctioned pop song of the mid-60s that sounds somewhere between The Beatles and The Carpenters—the chorus for which, my guide says, is Somebody loves me; the next is weirder still—1970s Funk with an east European flair.

At that point the authorities wanted to promote the idea that everything was ok, just normal, that there wasn’t a need for propaganda, and so we had Soviet sanctioned pop music though you will notice that it is really just local variations of western music, which is what people were trying to listen to anyway.

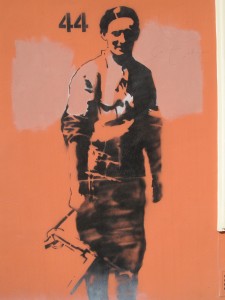

History hangs heavily over Poland and you really cannot escape it—the events are not abstract memory, they are a part of national consciousness that everyone knows and references as though they had just happened. In Warsaw those events are more awful, more complete than almost anywhere else; the capital city, a proud metropolis and centre of historical experience and architectural expression was levelled by the German army in 1944 following the Warsaw Uprising, the destruction of buildings proceeding according to their importance to Polish history and culture and continuing street by street and neighbourhood by neighbourhood. Pictures of the city afterword reveal a wasteland—piles of bricks and a few gutted, half standing buildings. No modern city has experienced a destruction more complete.

History hangs heavily over Poland and you really cannot escape it—the events are not abstract memory, they are a part of national consciousness that everyone knows and references as though they had just happened. In Warsaw those events are more awful, more complete than almost anywhere else; the capital city, a proud metropolis and centre of historical experience and architectural expression was levelled by the German army in 1944 following the Warsaw Uprising, the destruction of buildings proceeding according to their importance to Polish history and culture and continuing street by street and neighbourhood by neighbourhood. Pictures of the city afterword reveal a wasteland—piles of bricks and a few gutted, half standing buildings. No modern city has experienced a destruction more complete.

That wasteland was a tabula rasa for the new Soviet rulers in post-war Poland who set out to build a socialist realism urban landscape. The centre piece of that effort is the monolithic Palace of Culture, an enormous wedding cake sky scraper which, a direct gift from Stalin, can be scene from any corner of Warsaw, a symbol of domination if there ever was one, sited on a grande allée on which state power could be paraded. More to its credit, the government also oversaw the rebuilding of the old town and much of the historic centre, a painstaking, pedantic exercise, something the communists were actually quite good at, and involved reconstructing every single building based on photographs and historical records.

That wasteland was a tabula rasa for the new Soviet rulers in post-war Poland who set out to build a socialist realism urban landscape. The centre piece of that effort is the monolithic Palace of Culture, an enormous wedding cake sky scraper which, a direct gift from Stalin, can be scene from any corner of Warsaw, a symbol of domination if there ever was one, sited on a grande allée on which state power could be paraded. More to its credit, the government also oversaw the rebuilding of the old town and much of the historic centre, a painstaking, pedantic exercise, something the communists were actually quite good at, and involved reconstructing every single building based on photographs and historical records.

The mangled, recreated city that emerges from this now is still a remarkably pleasant one, with the buzz and vitality befitting a capital. But, as with many things Polish, the sense of loss that accompanies Warsaw is inescapable. Something else used to be here and the memory of that is not let go.

This street we are standing on—it used to be the centre of the pre-war city. There was a famous theatre, and behind it a square with cafes, and leading off of it residential streets with nice houses—a good neighbourhood.

The street I am on with the guide is not necessarily unpleasant, it is a wide avenue lined with post-war low rise granite buildings forming a shopping colonnade flanking a wide boulevard on the corners of which are statues of gargantuan women and men, sculpted in socialist realism style, wielding hammers and spades.

You see that Church there, the one hidden on three sides by high rise apartment blocks? This is not accidental—the Soviet planners tried to block out views of the Churches that remained standing. The Church stood on a large square, it was a lovely spot, apparently.

At this the guide flips open a note book with a black and white photo from the 1930s of a busy street filled with people and lined with gorgeous buildings, an Art Nouveau and neo-Baroque confection befitting the brief golden era of free and independent inter-war Poland. These memories are what remains and are kept alive. My tour guide is not an old man recalling past glory, he is a young Polish university student making some extra money, but the recall of the lost city is not uncommon, nearly every Pole will tell you the same.

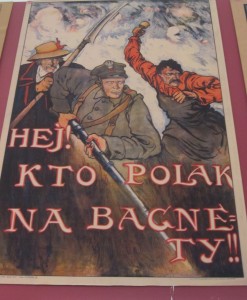

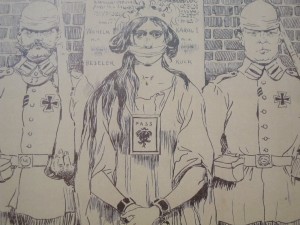

Countries with their own, tragic, history of suffering and strife imbue themselves with a national character shaped by the experience. In Poland’s case the single, inescapable, line of historical narrative is the experience of foreign oppression, centuries of invasion and subjugation. In the 18th and 19th centuries that included Russian, Austro-Hungarian and Prussian rule, partition and dismemberment. From 1795 to 1919 Poland disappeared entirely as an independent nation state. Russian domination and “Russification” was the dominant experience, was bitterly opposed and was marked by—tragically unsuccessful—rebellions in 1830 and 1863.

Countries with their own, tragic, history of suffering and strife imbue themselves with a national character shaped by the experience. In Poland’s case the single, inescapable, line of historical narrative is the experience of foreign oppression, centuries of invasion and subjugation. In the 18th and 19th centuries that included Russian, Austro-Hungarian and Prussian rule, partition and dismemberment. From 1795 to 1919 Poland disappeared entirely as an independent nation state. Russian domination and “Russification” was the dominant experience, was bitterly opposed and was marked by—tragically unsuccessful—rebellions in 1830 and 1863.

Polish nationalism endured these long dark years and is credited with developing a kind of quasi-religious romanticism, a national identity sanctified by suffering. Poles throughout insisted on the western and Catholic character of the country and rejected eastern Slavic influence. The country also developed a penchant for turning to outside salvation, almost always betrayed and ending badly. Poles joined Napoleon’s armies with enthusiasm on the promise of independence, although they were essentially used as mercenaries sent to suppress slave revolts in Haiti, fight the Peninsular War in Spain, and participate in the advance on—and retreat from—Moscow. Some senior officers loyally joined the Emperor Napoleon in exile on Elba. During the Second World War the Polish government went into exile in London, its airmen flew in the Battle of Britain—with distinction—and its army fought in the Normandy invasions and elsewhere before being betrayed at Yalta and delivered up to Stalin. After Soviet rule was imposed on post-war Poland the government in exile remained in London and met every two weeks for the next 45 years, only being dissolved in 1990 when it returned the official seals of the pre-war government to Warsaw after the first democratic elections.

Polish nationalism endured these long dark years and is credited with developing a kind of quasi-religious romanticism, a national identity sanctified by suffering. Poles throughout insisted on the western and Catholic character of the country and rejected eastern Slavic influence. The country also developed a penchant for turning to outside salvation, almost always betrayed and ending badly. Poles joined Napoleon’s armies with enthusiasm on the promise of independence, although they were essentially used as mercenaries sent to suppress slave revolts in Haiti, fight the Peninsular War in Spain, and participate in the advance on—and retreat from—Moscow. Some senior officers loyally joined the Emperor Napoleon in exile on Elba. During the Second World War the Polish government went into exile in London, its airmen flew in the Battle of Britain—with distinction—and its army fought in the Normandy invasions and elsewhere before being betrayed at Yalta and delivered up to Stalin. After Soviet rule was imposed on post-war Poland the government in exile remained in London and met every two weeks for the next 45 years, only being dissolved in 1990 when it returned the official seals of the pre-war government to Warsaw after the first democratic elections.

These experiences form the bed rock of Polish history and identity. National museums, which are the tableaus for telling the tale of creativity and pluck of any nation, are in Warsaw crowded by the sheer number devoted exclusively to foreign oppression: The Museum of the Independence Struggle—versus Czarist, Prussian, Austro-Hungarian rule—the Warsaw Uprising and Polish Resistance Museum, the Jewish Holocaust Museum, the Gestapo Head Quarters—spookily well preserved—the museum of the Soviet Occupation and the Museum of Father Jerzy Popietuzkow—the latter an anti-communist priest murdered by the security service in the 1980s. There is also a prominent statue in Warsaw to Ronald Reagan—the Gipper is revered for his services to defeating communism—as well as to Winston Churchill. There is a reason why the collapse of communism began in Poland—the farce of Soviet control could not extinguish the historical memory kept alive by Poles.

These experiences form the bed rock of Polish history and identity. National museums, which are the tableaus for telling the tale of creativity and pluck of any nation, are in Warsaw crowded by the sheer number devoted exclusively to foreign oppression: The Museum of the Independence Struggle—versus Czarist, Prussian, Austro-Hungarian rule—the Warsaw Uprising and Polish Resistance Museum, the Jewish Holocaust Museum, the Gestapo Head Quarters—spookily well preserved—the museum of the Soviet Occupation and the Museum of Father Jerzy Popietuzkow—the latter an anti-communist priest murdered by the security service in the 1980s. There is also a prominent statue in Warsaw to Ronald Reagan—the Gipper is revered for his services to defeating communism—as well as to Winston Churchill. There is a reason why the collapse of communism began in Poland—the farce of Soviet control could not extinguish the historical memory kept alive by Poles.

I will admit to a fondness for Poland, which comes from fondness for other places that have taken wrong turns in history that deprive them of their destiny, Africa among them. In Poland at least there is a happy ending—a country abused and dismembered, treated to the worst cruelties of war, genocide and despotism, now finds itself living in a golden age: free, democratic, capitalist and prosperous, anchored in NATO and the EU and fulfilling its historical destiny.