Sub-Saharan Africa will end 2004 as it has for most of the past decade—underperforming economically, and wracked by mal-governance and declining living standards. Home to a disproportionate share of the world’s failed and failing states, the UN will report that many African states have fallen in the global ranking of human development, continuing the trend since 1990 when real incomes per head have fallen 0.4% per year on average. None of this is inevitable, and the consequences of economic and political failure will never have been graver. But a small but growing number of states will grasp the opportunities available to consolidate macro-economic stability, attract investment and aid, increase growth and reduce poverty—proving that good governance can produce results in Africa as easily as elsewhere. Mozambique’s economwy will grow by 8%–close to its average for the previous 11 years. Ghana, Tanzania, Uganda, Botswana, Cape Verde, Rwanda, Mauritius and other relatively well governed countries will achieve steady growth, and reduce poverty. Africa will also feature disproportionately among the world’s fastest growing economies, with four countries in the top 10. That will include the fastest, Chad, with a mind-boggling 58% growth rate in 2004 as it pumps up as the continent’s newest oil producer.

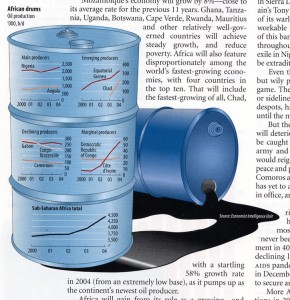

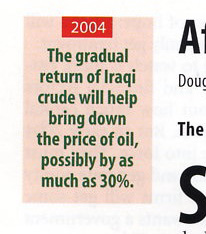

Africa will gain from its role as a growing supplier of oil, particularly the US which has been quick to spot a strategic opportunity. Oil exports will rise by 14%, led by Nigeria and Angola. But there will be increasing attention for Africa’s emergent producers, Equatorial-Guinea, Chad and, later, São Tomé. Oil will help counter Africa’s global marginalisation, although critics will point out—correctly—that Africans will see few benefits from the capital-intensive oil sector, which employs few people, has few links to the rest of the economy, and tends to fuel corruption. Angola’s corruption prone, oil rich government—which has requested a programme from the IMF despite having refused to implement its previous one—will be a test of the IMF’s ability to make an African government take poverty reduction seriously.

Africa will gain from its role as a growing supplier of oil, particularly the US which has been quick to spot a strategic opportunity. Oil exports will rise by 14%, led by Nigeria and Angola. But there will be increasing attention for Africa’s emergent producers, Equatorial-Guinea, Chad and, later, São Tomé. Oil will help counter Africa’s global marginalisation, although critics will point out—correctly—that Africans will see few benefits from the capital-intensive oil sector, which employs few people, has few links to the rest of the economy, and tends to fuel corruption. Angola’s corruption prone, oil rich government—which has requested a programme from the IMF despite having refused to implement its previous one—will be a test of the IMF’s ability to make an African government take poverty reduction seriously.

Several of Africa’s long-running wars and civil conflicts will move to resolution, as peace takes hold and post-conflict recovery gets underway. Peace in the Democratic Republic of Congo will consolidate, defying expectations that this complex multi-country and multi-party conflict could be insoluble. Although its cumbersome new unity government comprising dozens of different groups—five of them armed—will be a fractious affair, they will do just enough to keep the agreement together as prepartations for elections begin near the end of the year. Donors will pour in further money, adding to the more than US$2.5bn already pledged or disbursed, underpining a post-war boom.

Post-conflict recovery, albeit imperfect, will consolidate in Sierra Leone, paying handsomely the risky intervention made by Tony Blair and UN peace keeping forces in this ex-failed state. Liberia, rid of its war-lord president, Charles Taylor, should begin a workable, if at times messy, peace, ending the baleful influence of this bandit state which has spread war and instability throughout West Africa for a decade. To watch for: Mr Taylor, now in exile in Nigeria, may become Africa’s first head of state to be extradited for war crimes.

Look for an endgame to the tragedy of Zimbabwe under its appalling but wily president, Robert Mugabe. Although Mr Mugabe has defied expectations,to hang on, the chances are that he will be gone, or sidelined, by the end of the year even if, like so many despots, his grip on power appears unassailable up until the moment it collapses entirely. Hopeful of Mr Mugabe’s departure, South Africa will continue its quiet diplomacy, mindful that the first rule of African states is public solidarity with fellow incumbents, no matter how unworthy. Côte d’Ivoire will deteriorate further in 2004. Embattled president Laurent Gbagbo, stalling on implementing a January 2003 peace agreement, will be caught between two intransigent factions: his own army and the rebels. Doing enough to satisfy either would reignite war or spell his own end. Four decades of peace and prosperity are an increasinly distant memory.

Zimbabwe and Côte d’Ivoire’s misery will be reminders of Africa’s volatility—few would have predicted that what until recently were its strongest states would now, and so quickly, be so wretched. There are other candidates to join them in collapse and instability in 2004. Guinea-Bissau under its volatile, but democratically elected, president Kumba Yala, retains a strong likelihood of experiencing a coup in 2004, as does Comoros, or Burundi where the Tutsi-dominated army has yet to allow a Hutu head of state serve a full term in office.

Between the extremes of Africa’s success stories and its even fewer—but attention grabbing—war zones, the majority of African countries will muddle through, under-performing and missing opportunities, but maintaining political stability and entrenching national elites. Africa’s most typical country in 2004 will be Malawi, which has never been at war, has had only one change of government in 40 years, and experiences economic stagnation, declining living standards and the ravages of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. President Bakili Maluzi will step down in December, reluctantly accepting defeat in attempts to secure an unconstitutional third term. Other heads of state to go in 2004 include Namibia’s Sam Nujoma, not expected to change the constitution for a second time to accommodate a fourth presidential term. Guinea-Conakry’s ailing president Lansana Conté may die in office, having done little to appoint a successor and prepare an orderly transfer of power.

More African countries will hold democratic elections in 2004 that can be termed free and fair, even if they are predictably won by incumbent governments. South Africans will go to polls in September, that will be won handily by the governing African National Congress and President Thabo Mbeki, who will enter his final term in office. Botswana’s government will be returned to power in October as will Ghana’s president John Kufour who—more frequently in Africa than before—heads a government that displaced a long-entrenched one and is completing a first, and relatively successful, term in office. Mozambicans will vote for the third time since emerging from civil war in the early 1990s.

South Africa will be a force for growth and stability as the continent’s unsung peace-negotiator-in-chief, seeking an end to conflicts, fielding peace keeping troops in Congo and Burundi, and encouraging better governance through the New Parternship for Africa (NEPAD), the compact with western governments designed to attract greater aid and investment. South African firms will continue their investment drive into Africa, providing some of the only capital and management expertise these countries can attract. It will also lead African participation in the next round of trade negotiations at the WTO, seeking improved access to rich world markets and reduced western agricultural subsidies that damage Africa’s farmers. Mindful of marginalisation, it will push fellow governments to engage, build trade capacity and expand rather than withdraw their participation in the global trading system. It will be an uphill struggle: many are already threatening to pull out rather than seize what is on offer.

Douglas Mason is an editor in the Africa department of The Economist Intelligence Unit