Maré favela, Rio de Janeiro October 2011

The slums—or favelas—of Brazil’s cities as seen through movies and pop culture are generally places of unspeakable brutality. From City of God—the 2002 film that tells the—mostly—true story of the short brutish lives of a group of young gang members to the 2007 Tropa de Elite about the urban combat of a favela bound police unit, these stories depict an urban horror of violence and crime. These are not places you are supposed to visit and would lead to certain robbery or worse at the hands of heartless criminals and indifferent residents if you do, according to popular imagination.

The slums—or favelas—of Brazil’s cities as seen through movies and pop culture are generally places of unspeakable brutality. From City of God—the 2002 film that tells the—mostly—true story of the short brutish lives of a group of young gang members to the 2007 Tropa de Elite about the urban combat of a favela bound police unit, these stories depict an urban horror of violence and crime. These are not places you are supposed to visit and would lead to certain robbery or worse at the hands of heartless criminals and indifferent residents if you do, according to popular imagination.

With this in mind it is reassuring to know after two weeks in one large and notorious favela in Rio de Janeirio that these are mostly peaceful and even pleasant places with normal, kind and resourceful people going about their daily lives. There is far more joy than suffering apparent here.

Maré favela is located near the port on low lying ground next to an eight lane highway that leads from Rio de Janeiro’s international airport toward the elite southern suburbs of Ipanema and Leblon. It has neatly laid out, but narrow, streets and almost all homes are brick and concrete structures with electricity and running water. There are busy commercial areas with shops and supermarkets, restaurants and a general air of peace.

That peace comes from somewhere and comes at a price. The favela is controlled by drug gangs. This is a strong but mostly unseen power structure, a parallel state. The rest of modern and beautiful Brazil is held at bay and little can happen here without the explicit endorsement of the gangs. Like feudal lords the gangs provide protection and order, even meet social obligations. In return there is obedience and, when necessary, tribute. Provided they do not interfere with the trade, cooperate with the police or challenge the gangs, people are mostly left alone. The presence is hardly benign, however, and this favela, like many others, has sky high levels of violence, most of it involving the young men drawn into the drug trade by its obvious material and other temptations in a poor community but, also, bystanders caught in the cross fire of the regular gun battles between the gangs and the police or between the gangs themselves. In Maré this is claimed to be one of the highest of any favela in Rio. During the time I am here a resident is quoted in a newspaper saying the following:

Sometimes you get home and you can’t enter the neighborhood because of the shooting. Or you want to go out and you can’t…you lie on the floor or you protect yourself as best you can. The worst part is that you think you’ll get used to it but you never do. What makes me the angriest is because we’re not in Zona Sul (Rio’s elite, or at least main stream, neighbourhoods) the media doesn’t worry about it. This happens all the time but it’s like we don’t exist, like we’re not a part of Rio de Janeiro; Maré is a forgotten place.

Favelas in Brazil are generally under the control of the local affiliates to large national level gangs involved in the trans-national drug trade. In Maré there are two—a third was crushed in a turf battle—of which the best organised is Commando Vermelho—the Red Command—established by jailed left wing revolutionaries in the 1970s. Today the gangs are still run by, or together with, jailed leadership who even launch large security operations together when their joint interests are threatened. Less than a year ago, during the famed November 2010 Rio de Janeiro Security Crisis, the gangs launched coordinated violent attacks in public areas and elite neighbourhoods of the city over a one week period, intended to deter the government from proceeding with security operations in the favelas. Over 180 vehicles were burned and 40 people killed. No movie has been made about this violent affair yet but it followed a previous campaign in the city of São Paulo, also directed from inside prison by jailed gang members, and which resulted in the authorities backing down. A subsequent, popular, movie, chronicles that episode.

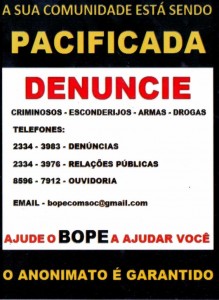

The current source of the drug gangs ire is an ongoing government campaign to “pacify” the favelas, a massive security operation involving initial invasions followed by a large permanent police presence, carried out by the Unidades de Polícia Pacificadora. The pacification campaign has been proceeding slowly, favela by favela, and has produced mixed results although it is credited with, eventually, lowering the overall level of violence and pushing the drug trade out of view.

The pacifications are backed by an elite police unit, Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais (BOPE) known as “bop-ee” which, despite its sing-songy name that sounds like a children’s rhyme, is a brutally effective unit drawn from the military. It is brought in for the pacification operations in place of the Rio de Janeiro city police, considered too corrupt and compromised by the drug trade. The BOPE use heavy weapons, armoured cars and military helicopters in their operations.

Maré has not yet been pacified but it is understood to be next on the list. Already it has been affected by pacification campaigns elsewhere and drug gangs fleeing from a neighbouring favela attempted to invade Maré but were repulsed after fierce gun battles. The level of violence and instability in Maré has been high over the past month and there is a steady increase in tension during the time of my visit, with police incursions nearly every day, announced, invariably, by fireworks or gun fire from the roof tops by gang look outs.

Policing in the favelas is controversial for many reasons but most obviously for it being imposed on communities rather than with them via the cooperative policing models that now constitute best practice internationally. Police operations are generally seen as invasions with sudden incursions by a large heavily armed force and the closing of all exits from the favela followed by the seizure of a target, a gun fight, and subsequent withdrawal.

The police are not loved here and are blamed for the civilian casualties that result from their operations which are, essentially, urban warfare. They are also alleged to be corrupt and violent themselves and even complicit in drug and arms trafficking. Extortion is said to be common with one popular wheeze being the arrest of gang members who are held without charge until they can pay up. The violent, dangerous, favelas are not sought after positions for the police and a posting here is regarded to be a punishment. Until recently Maré’s police chief was someone who had been transferred after being accused of complicity in the murder of a judge. But much as the police are despised and distrusted, people do not like the violent rule of the drug gangs either. That is something to keep in mind when hearing of police malfeasance; working as a policeman in the violent favelas of Rio de Janeiro is a dangerous, thankless, task if there ever was one. The rule of the drug gangs is a social evil with ghastly consequences for what are very poor communities and the obligation of the state to end this is not something that will be achieved painlessly.

One person who has a front seat on these violent struggles is the community liaison officer employed by the boxing and youth development NGO, Luta Pela Paz, which is hosting me here. Uniquely, he has unimpeded access to all areas of the favela and is trusted to deal directly with all the drug gangs and armed factions, the police or anyone else. If anything happens, he is the first to know, the first to have to deal with messy and unpleasant situations and people. Looking at his dark eyes and wise, somewhat weary, disposition I suspect that this is someone who has seen many things. Now elderly he is wheel chair bound, having been crippled during his own time as a youthful gang member.

One person who has a front seat on these violent struggles is the community liaison officer employed by the boxing and youth development NGO, Luta Pela Paz, which is hosting me here. Uniquely, he has unimpeded access to all areas of the favela and is trusted to deal directly with all the drug gangs and armed factions, the police or anyone else. If anything happens, he is the first to know, the first to have to deal with messy and unpleasant situations and people. Looking at his dark eyes and wise, somewhat weary, disposition I suspect that this is someone who has seen many things. Now elderly he is wheel chair bound, having been crippled during his own time as a youthful gang member.

A man of African background he speaks of this and other favelas as a continuity in Brazil’s long history of marginalised, neglected communities, and points to the origins of favelas in Rio as the refuge of fugitive African slaves, and draws parallels with the autonomous slave republics established in the interior of the north-east during the 18th century. He speaks with passion but some sadness about the lost potential of youth in the favela, economic and social marginaliation, the violence of the drug gangs but, also, the police, who he clearly sees as the primary manifestation of the modern state in this area. One of his many roles for the Luta Pela Paz project is to reach out to youth in the gangs and says he begins by asking them of their former dreams, their former selves, before they became part of the drug trade.

After my first week in Maré the long awaited police pacification campaign begins on a Friday afternoon, announced by a military helicopter dropping leaflets over the favela stating that the community is being pacified. There is some dread about this prospect and the community is in an state of agitation over what will probably be a violent struggle, a change of power. Passing the project’s community liaison point man in the hallway of the Luta Pela Paz building, a source of light in this community, he wears the expression of a man preparing for a war. Climbing into our van to leave the favela for the night, there is a BOPE armoured car up ahead of us. The street looks deserted. One of the project officers who is hitching a ride home with us, leans forward and directs the driver to turn off the road and leave the favela by another exit.

After my first week in Maré the long awaited police pacification campaign begins on a Friday afternoon, announced by a military helicopter dropping leaflets over the favela stating that the community is being pacified. There is some dread about this prospect and the community is in an state of agitation over what will probably be a violent struggle, a change of power. Passing the project’s community liaison point man in the hallway of the Luta Pela Paz building, a source of light in this community, he wears the expression of a man preparing for a war. Climbing into our van to leave the favela for the night, there is a BOPE armoured car up ahead of us. The street looks deserted. One of the project officers who is hitching a ride home with us, leans forward and directs the driver to turn off the road and leave the favela by another exit.