The Independent, London 7 March 2003

The Independent, London 7 March 2003

Quentin George Keynes, film-maker and book collector: born London 17 June 1921; died Cambridge 26 February 2003

In 1937 Quentin Keynes climbed to the roof of his family’s house in Hampstead and refused to come down until his parents agreed he needn’t return to boarding school. It was a wilful choice for a 16-year-old, and one he followed for the rest of his life – he would not be told what to do.

The mould of English public school, Oxbridge and the career expected in an over-achieving family were all refused. Instead there was a pursuit of the unusual, the remote, and the obscure, infused with a mixture of boyish enthusiasm, startling naïveté, keen insight and a sharp intelligence. There were real accomplishments, but they defy conventional description: film-maker, explorer, lecturer, African safari leader, book collector, and connoisseur of rare sports cars.

Interests were pursued with curiosity and impulsiveness, unscholarly but astute. His books and manuscripts – ranging from David Livingstone, Sir Richard Burton and Charles Darwin to James Joyce and Ezra Pound – are acknowledged to be among the foremost private collections, and, with respect to the Africana, of considerable historical importance. In the best English tradition, he bristled at the idea that he ever bought anything out of concern for its financial value. He valued what was of particular interest and then felt the need to collect everything associated with it.

Connections counted, and were traded on in a way that would now be considered politically incorrect or impolitic. There was much to trade upon: his mother’s grandfather was Charles Darwin, his father the renowned surgeon and bibliographer Sir Geoffrey Keynes, and his uncle the great John Maynard Keynes. It was a charmed life of privilege, or privileged associations; for a man whose great-grandfather’s picture is on the £10 note it was accepted as the natural order of things. Among his personal effects are letters from Jackie Kennedy Onassis and his fellow members of the Roxburghe Club, and a Virgin Atlantic bag full of dried African elephant dung.

In 1939, as Europe slipped toward war, he joined the British embassy in Washington through a connection of his uncle Maynard’s; and it was in America that he found his way. With a distinguished surname, tall and handsome, wartime Washington was à go-go for a young English blue-blood – cocktail parties, a dalliance with one of the Roosevelt children, Hollywood acquaintances and the débutante ball of Jackie Bouvier. Back home his three brothers did National Service or dug potatoes.

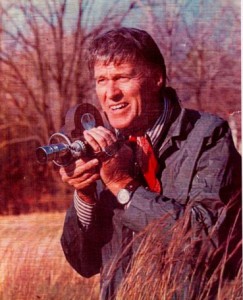

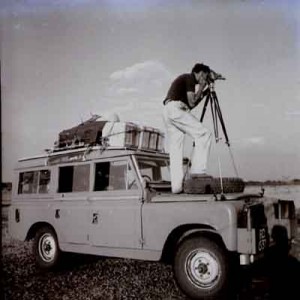

But it was in Africa and equatorial islands that Keynes made a name for himself, embarking on his first adventures in the late 1940s and beginning to film wildlife and whatever he saw. In 1950, he moved among the nomadic Ovahimbas of the Kaokoland in Namibia and photographed the wreck of the Dunedin Star on the Skeleton Coast, the scene of a famous wartime shipwreck rescue. Four years later, in Angola, he became the first person to capture the rare Giant Sable antelope on film. For long he was the last, as war closed the countryside. Only in 2002, as the country emerged from over three decades of conflict, were remnant populations confirmed. He showed equal passion for the pursuit of the prehistoric coelacanth fish in the Comoros Islands, as well as filming in the Galapagos, the Falklands and St Helena.

But it was in Africa and equatorial islands that Keynes made a name for himself, embarking on his first adventures in the late 1940s and beginning to film wildlife and whatever he saw. In 1950, he moved among the nomadic Ovahimbas of the Kaokoland in Namibia and photographed the wreck of the Dunedin Star on the Skeleton Coast, the scene of a famous wartime shipwreck rescue. Four years later, in Angola, he became the first person to capture the rare Giant Sable antelope on film. For long he was the last, as war closed the countryside. Only in 2002, as the country emerged from over three decades of conflict, were remnant populations confirmed. He showed equal passion for the pursuit of the prehistoric coelacanth fish in the Comoros Islands, as well as filming in the Galapagos, the Falklands and St Helena.

His Africa was essentially the continent of the late colonial period: letters of introduction to governors and camping on the ground amid wild game almost before the first national parks were set up, without guides, guns or a tent. Little changed for him over the next 50 years; the great moral and political issues of modern Africa were generally ignored, luxury game lodges disdained. This was no Wilfred Thesiger, or Leni Riefenstahl, glorying in the tribal or the primitive; while he was impressed by the bushmen, it was the wildlife that interested him. His Africa was in many ways closer to that of the Victorian explorers, of Burton and Speke, Stanley and Livingstone, whose initials he discovered on the banks of the Zambezi river in Mozambique, carved inside a baobab tree.

The analogy goes further. This ebullient but intensely private man was in many ways an anachronism from the Victorian era: sexless, or asexual, eschewing family or married life, he subsumed his energies and drive in the pursuit of the unusual and the indulgence of his own interests. He had few encumbrances and recognised few responsibilities. Those left to pick up the tab recall the self-absorption of a man who would rarely reach for a restaurant bill, or the friend who came to stay, and stayed. His beautiful manners, an adolescent enthusiasm and almost naïve purity meant that much was forgiven.

It is as a guide, raconteur and safari leader that Quentin Keynes may be best and most fondly remembered. For 50 years touring the private schools of England and North America, showing his adventure films, he brought, or introduced, Africa to countless boys and girls. The tales of waking among lions prowling in the camp, being chased up a tree by a rhino or his search for the spotted zebra, which he filmed in 1964, had a magical effect on the young. Each year a few of the boys would accompany him on his famous expeditions, as willing camera bearers, acolytes and go-fors. Many would go on to distinguished careers in wildlife exploration and film-making.

At 81 he was planning his next trip when cancer took hold. Jackie Onassis, a lifelong acquaintance, wrote to him in 1994, “I so admire the verve with which you live your life.”

At 81 he was planning his next trip when cancer took hold. Jackie Onassis, a lifelong acquaintance, wrote to him in 1994, “I so admire the verve with which you live your life.”

Douglas Mason is an editor in the Africa department of The Economist.

thanks for this Doug

A very moving obituary bringing back memories of stories told. Futzak! (it was futzak, was it not?)

It is “voetsek” I believe.