September 14th 2011

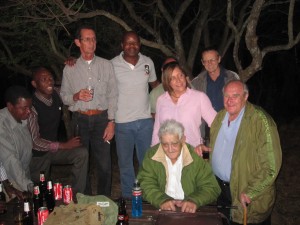

Die Bos—“The Bush” in Afrikaans—outdoor pub is situated in a hollow under a forest of thorn trees and, with a copper moon rising above the tree line on a summer evening, is a suitable setting for gathering the veterans of the bush wars of South Africa’s late apartheid period. What is called “The Border War” was the last, but nasty, gasp of the apartheid era, a pitiless 13 year conflict fought inside Angola and near the border with Namibia, the latter at the time a quasi colony ruled by South Africa in defiance of international law.

Die Bos—“The Bush” in Afrikaans—outdoor pub is situated in a hollow under a forest of thorn trees and, with a copper moon rising above the tree line on a summer evening, is a suitable setting for gathering the veterans of the bush wars of South Africa’s late apartheid period. What is called “The Border War” was the last, but nasty, gasp of the apartheid era, a pitiless 13 year conflict fought inside Angola and near the border with Namibia, the latter at the time a quasi colony ruled by South Africa in defiance of international law.

Viewed, variously, as a proxy of the Cold War with white ruled South Africa facing off against Soviet and Cuban forces; as a battle for black majority rule in South Africa itself; or, essentially, as a civil war inside Angola among the groups claiming the right to rule, The Border War was an epochal conflict in late 20th century Southern Africa. It ended in a tactical stalemate but a strategic defeat. Apartheid South Africa could not subdue Angola or the other front line states or determine who they would be ruled by. But, as the Soviet Union and eastern block collapsed, an opening was created for a peaceful settlement. Namibia achieved independence and black majority rule in 1990 followed, four years later, by the, still, marvelous social and political miracle that delivered the end to minority rule in South Africa itself.

For the men who actually fought the Border War on the South African side there is a mix of emotions associated with that time and what it means today. With South Africa’s politics now taking on a distinctly poisonous tone and the current ANC government under fire for corruption and illiberal approach to governance and democratic institutions, there is among this group a grim sense of satisfaction.

For the losing side of any war the wounds are deeper, the memory more vivid—they are still fighting the war. For the men gathered here this evening, the war is neither distant or abstract, it is the formative experience of their lives. Most make no claim to political sophistication or even real conviction, although there is an undeniable pride, defiance even, over something that has put them on the wrong side of history—the last defenders of the apartheid regime.

How much any of them acted on conviction is debatable. The motivation of men who staff militaries and fight wars often has little to do with political and other causes. Like boys hard-wired for risk, the male character will seek tests to ones mettle and find the fullest avenue for it in the military and in war time. Most of these men started as 18 year old conscripts, some going on to be permanent force members after acquiring a taste for soldiering, the sheer addictive power of team work and risk sharing under fire, intensive training, sophisticated equipment, specialised expertise, pride and esprit de corps, being something that kept them there.

How much any of them acted on conviction is debatable. The motivation of men who staff militaries and fight wars often has little to do with political and other causes. Like boys hard-wired for risk, the male character will seek tests to ones mettle and find the fullest avenue for it in the military and in war time. Most of these men started as 18 year old conscripts, some going on to be permanent force members after acquiring a taste for soldiering, the sheer addictive power of team work and risk sharing under fire, intensive training, sophisticated equipment, specialised expertise, pride and esprit de corps, being something that kept them there.

Johan is a well built man in his early 40s wearing a leather motorcycle vest with an “Airborne Riders” emblem on the back, a fraternity of military veterans with international chapters, and badges from the old South African army parachute brigade as well as its legendary reconnaissance—or recce—unit. What did he do during the war?

We were sent on missions behind the lines for up to 10 weeks at a stretch, a “Stick” of 4-8 men. We carried 35 kilos each, it was half my body weight at the time.

There is little bravado or aggressive rhetoric among these people; most are measured and rather gentlemanly although one source of restraint tonight is the presence of “The Colonel”, their former commanding officer, and the high minded fact that tonight’s gathering is his latest book launch, another addition to the canon of Border War Literature.

Colonel Jan Breytenbach is a legendary figure in South Africa, a professional soldier of maverick disposition; from an illustrious Cape Afrikaner family, one brother is the writer and anti-apartheid activist Breyten Breytenbach—jailed for treason for seven years by the white government—and another a prominent war correspondent, Cloete Breytenbach. Known as a brilliant, fearless, figure his achievements include having founded and led the South African army’s special forces unit, the Reconnaissance Commando, or “Recces”, but is best known for his role in forging and leading the odd-ball but remarkable 32 “Buffalo” Battalion, a unit made of Angolan soldiers drawn from the remnants of an anti-colonial guerilla movement, Force National por Liberation du Angola (FNLA).

Colonel Jan Breytenbach is a legendary figure in South Africa, a professional soldier of maverick disposition; from an illustrious Cape Afrikaner family, one brother is the writer and anti-apartheid activist Breyten Breytenbach—jailed for treason for seven years by the white government—and another a prominent war correspondent, Cloete Breytenbach. Known as a brilliant, fearless, figure his achievements include having founded and led the South African army’s special forces unit, the Reconnaissance Commando, or “Recces”, but is best known for his role in forging and leading the odd-ball but remarkable 32 “Buffalo” Battalion, a unit made of Angolan soldiers drawn from the remnants of an anti-colonial guerilla movement, Force National por Liberation du Angola (FNLA).

As Portugal withdrew from its former colony, Angola, in chaos in 1976, three liberation movements fought to become the country’s first independent government. After being crushed in fighting in the capital—the stronghold of the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA)—the group that went on to gain power and continues to do so 35 years later—the FNLA eventually imploded, its remnants being incorporated into the South African army and what is known affectionately as “Three-Two”.

Adjectives associated with 32 include: elite and secret but, also, expendable. At a time when information on the border war was withheld from the public but the government was sensitive to white military casualties, Buffalo Battalion gained a reputation for being the unit given the hardest tasks. It also served as a kind of quasi penal unit in the South African army, taking in officers and soldiers unfit for more conventional units as well as deserters and miscreants offered jail or service in Three-Two. Also included among its number were volunteers and mercenaries from Australia the UK and US. In short, The Dirty Dozen of the Border War, despised by the conventional South African Army as a mostly black unit, and hated by the anti-Apartheid forces as traitorous sell-outs.

Journalistic and academic treatment of southern Africa during the period of liberation tends to grant exclusive moral status to the African political and military groups who came out on top or became the opponents of apartheid South Africa. For those who ended up on the wrong side of history, this is a resented outcome. The history of Angola’s liberation struggle has a degree of arbitrary treatment regarding the political and moral legitimacy of the MPLA versus its domestic opponents who also fought for independence against the Portuguese colonial power. All three groups regarded themselves as left wing and revolutionary and all had an essentially ethnic basis, with the MPLA drawing disproportionate support among urban mulattos versus the more explicitly African origin of the FNLA and the third guerilla group, União Nacional para a Independencia Total de Angola (UNITA). But once African states decided to recognise the MPLA as Angola’s first government—a tie breaking vote decided by Idi Amin—and the FNLA and UNITA had gone on to strike up their tactical alliance with South Africa, a deal with the apartheid devil, the die was cast: only one of these groups would be accorded recognition and status versus the also rans. In power the MPLA went on to establish a one party Marxist state responsible for political and human rights abuses as well as—in this highly oil rich country—legendary corruption and misrule.

The rump FNLA as represented by 32 Battalion also fought alongside arch rival UNITA, the larger and more successful Angolan rebel movement which also accepted the support of South Africa in its bitter, hateful conflict with the Angolan government. Even after the demise of the apartheid regime, the Angolan conflict between UNITA and the government continued, ferociously, for another seven years.

In the historical narrative that all southern African liberation movements have established, including Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Namibia and, even South Africa itself, the ruling party is accorded the role of heroic nation builder, their rivals, criminals and imperialist stooges. It is indisputable that these movements delivered freedom, defeated colonialism and white minority rule. The problem comes in the character of the governments that followed, in the political hegemony mercilessly enforced, in the exclusion of other forces and hostility to pluralism—underpinned by the belief that other voices are not legitimate. They have also come to believe that delivering independence is something that confers political legitimacy in perpetuity. Decades later any of them have still to allow real political pluralism or an election they might lose, to become, in other words, normal democracies in which there are regular changes of power and political opponents are respected as legitimate forces rather than reviled as traitors and villains.

But it is in the silencing of other voices and the battle to control the interpretation of history that the liberation movements are at their most vulnerable and most pernicious. The chronicle of history is a powerful thing and is tightly guarded by these parties which write the school history text books and impose their own account. The public in these countries must hear endlessly of the feats and sacrifices of liberation, whose names festoon streets and public holidays, making the ruling party inseparable from the country’s past. Excluded from the account are post-independence horrors that include political re-education camps for class enemies and secret execution of party dissidents (Mozambique, Angola), scorched earth campaigns against members and supporters of rival parties involving 10s of thousands of civilian deaths (Zimbabwe, during the late 1980s) or that the liberation movement concerned never actually gained the consent of the public for its rule through democratic elections for the first two decades or more of independence until forced to by a UN peace settlement (Mozambique, Angola).

From control over historical narrative flows entitlement—these parties rule in their own interests, a liberation aristocracy who dominate government, staff senior departments and state corporations, are first in line for black empowerment deals that grant preferred local partners for foreign business, reward themselves handsomely. One can look no further than the tragedy of present day Zimbabwe to find the abuses that “struggle credentials” are put to justify political exclusion and self-interest.

With the demise of apartheid, 32 Battalion was disbanded and its former members and their families dumped in the small settlement of Pomfret, an isolated, hard scrabble area in South Africa’s arid Northern Cape Province. A proud, if politically incorrect community, it has been battling attempted eviction by South Africa’s current ANC government which regards them as an affront to its own liberation era loyalties. The unit, deployed in South Africa’s black townships with predictable results, was broken up on the insistence of the ANC during the transition to majority rule.

In an exercise of historical fiction it would be easy to imagine what might have happened had the FNLA rather than the MPLA come out on top in Angola’s liberation struggle. Might there now be from among the down-trodden members of this community, prosperous cabinet ministers and businessmen, their children attending elite boarding schools in Europe, public squares named after them, their sacrifices extolled in the historical narrative? It is with good reason that African politics are regarded as zero-sum contests: the governing elite in Angola rewards itself lavishly; the Angolans in Pomfret live in shacks and are marginalised in every sense of the word.

Back at Die Bos, located in a suburb on the outskirts of Pretoria, the pub is serving up cheap beer, steaks and mealie pap to the veterans of 32 and the other old South African army units who have gathered tonight to recall old battles, fallen comrades, their own version of history.

João is a youthful looking 41 and began life as a soldier in Buffalo Battalion at age 16. The child of refugees who were displaced by fighting inside Angola, he grew up in a refugee camp in northern Namibia near the Angolan border before joining 32. He is one of several black former soldiers here at tonight’s gathering among what is a mostly white former officer corps. Articulate and confident, switching easily back and forth between Portuguese, English and Afrikaans, he is a man who might have been destined for greater things if fate—and history—had called differently. He now works as a security officer with international postings.

Most of the other black Angolan veterans of 32 are struggling and many are here picking up contacts and scratching for work opportunities. Their white comrades, most of them of working class backgrounds and who have been granted few favours in life, are not particularly prosperous either.

What are these old dogs of war doing now? Some continue to work in private security, are employed in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere. Others scrape along as contractors and tradesmen, garage door installers and small business owners. Several of those who are here tonight are quite elderly, limping with canes, and wearing sad, vacant, eyes.

What are these old dogs of war doing now? Some continue to work in private security, are employed in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere. Others scrape along as contractors and tradesmen, garage door installers and small business owners. Several of those who are here tonight are quite elderly, limping with canes, and wearing sad, vacant, eyes.

Apart from kvetching about the current black government most are quite harmless. But not all of them. One man here, William Ratte, is highly involved in white right wing politics, kind of an activist and figure head for the right. A former member of the efficient, but brutal, Rhodesian special forces, he served in 32 Battalion and was described by a senior officer as: “simply the finest, most professional soldier ever trained by the South African Defense Force.”

Now a bitter ender, but apparently a principled one, he has been involved in minor rebellions and suspected coup plots, been jailed for sabotage and theft of military weapons, launched legal challenges against the ANC government, has served several stints in jail, launched hunger strikes and led marches. Most famously, he was involved in an incident in parliament when he threw silver coins and yelled “Judas” at South Africa’s last white president, F.W. de Klerk, as power was being handed over to the majority through democratic elections.

Other people here are more neutral, even politically respectable South Africans. One, an elegant and petite woman, works as a public health professional for a major international NGO, but is here because her—beloved—late Father had been an officer in the Namibian police unit Koevoet, and recalls growing up as a child on military bases there during the 1980s.

Koevoet—which means crowbar in Afrikaans—was a counter insurgency para-military police unit in Namibia known for its brutality. At the time when Koevoet was active I was a young student at a Canadian university and a member of the campus Southern African solidarity campaign. We lobbied for the cause of the liberation movements, in the didactic way typical of university politics, excoriated the apartheid regime’s security forces, demonised Koevoet and 32 Battalion. When I mention this and that there is some personal irony to now being in the company of these veterans, someone reaches across the table and grabs my arm: “it is better that you don’t say that here”.

one of your best articles

A very, very moving post – you at your best (again)

You have no fear Douglas!

Thank you for the education and for sharing your passions.