April 17th 2011 Rushuru, Nord Kivu Democratic Republic of Congo

Are things getting better? No, no they’re not. Something can happen at any time and you never know when. We had 20 incident reports last month—something violent enough for us to become involved. Sometimes we think things are getting better for a while and then they fall apart again. Who is it? We never really know—bandits, rebels, the militias, the government army? All anyone can say is that it is men in uniform with guns and they all wear the same uniform. Most of the incidents are looting, rape and other violence. Out on the roads it is the looting of vehicles. Traveling at night is risky—those that do it know that.

Are things getting better? No, no they’re not. Something can happen at any time and you never know when. We had 20 incident reports last month—something violent enough for us to become involved. Sometimes we think things are getting better for a while and then they fall apart again. Who is it? We never really know—bandits, rebels, the militias, the government army? All anyone can say is that it is men in uniform with guns and they all wear the same uniform. Most of the incidents are looting, rape and other violence. Out on the roads it is the looting of vehicles. Traveling at night is risky—those that do it know that.

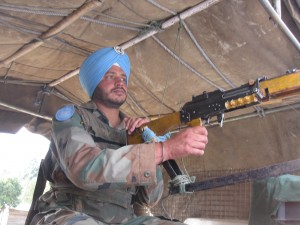

I am in the lead vehicle of a UN supply convoy when this bleak statement is delivered by a young Indian Army officer, Major Gupta, about our destination, Rushuru district in Nord-Kivu province. It is dark now and on mention of night time attacks he illuminates a red light on the dashboard.

This light is to let the bandits know it is the UN. They aren’t looking for a fight with us and it is not our job to engage them in combat either; that is the job of the FARDC, the government army. We can provide logistical support and back up, that is it. What we are supposed to do is follow up on the incidents that are reported to us or that we come across on our patrols.

It is almost disappointing to hear that the UN is actively avoiding confrontation with “the bandits” but their job is to prevent violent incidents, not provoke them. In UN speak this is a Chapter 7 mission, with full live fire capability to prevent human rights abuses and protect the civilian population. On that basis is has seen plenty of combat in the last decade. But now, increasingly, it’s role is to take a back seat to the government army, the FARDC, which is meant to shoulder responsibility for public security.

How is it doing with that responsibility? Not very well. Although the army has absorbed a decade’s worth of technical assistance from the UN and elsewhere it is still dogged with fundamental organisational problems—actually paying its own soldiers being one of them. Soldiers, when not paid, will take what they need. The army is also a rag tag group that has absorbed numerous armed groups into its ranks under various peace agreements but has not yet digested them into a coherent force.

How is it doing with that responsibility? Not very well. Although the army has absorbed a decade’s worth of technical assistance from the UN and elsewhere it is still dogged with fundamental organisational problems—actually paying its own soldiers being one of them. Soldiers, when not paid, will take what they need. The army is also a rag tag group that has absorbed numerous armed groups into its ranks under various peace agreements but has not yet digested them into a coherent force.

Rushuru is a troubled place and human rights abuses are daily occurrences. There are many possible culprits—the FDLR, a rebel group responsible for the Rwandan genocide; the psychotic Lords’ Resistance Army (LRA) from Uganda; the various Mai Mai militia groups and, more commonly, small bandit groups that may come from any of these groups plus the government army. Although it is only acknowledged quietly, it is the latter who are the most persistent source of human rights abuses in Rushuru and, indeed, most of eastern DRC. With the army responsible for much of the violent abuse in the area I ask Major Gupta if there has ever been a court martial of a FARDC soldier in this district, or any other in the province. He scoffs and says no, there is not. They don’t have the ability to force the army to prosecute its own.

They aren’t paid. It is only because we are paid and are comfortable that we follow the law and live with integrity. These people do not. A soldier receives $10/month, if at all, and an officer’s salary is $60.

This is the contradiction of the UN as it tries to execute its mandate of protecting the civilian population, upholding human rights and building capacity in the government army—it can’t call out what is obvious to everyone and instead has to work with a compromised institution.

You have to engage with them, you can’t go haranguing them that they are bloody useless if you are going to have leverage. We have good relations with the commanding officers, we go to them with problems and incident reports. Yes, there are times that we can’t say what we’d like or what the truth demands but this is a process and if there is going to be any hope of progress this is how it must work.

You have to engage with them, you can’t go haranguing them that they are bloody useless if you are going to have leverage. We have good relations with the commanding officers, we go to them with problems and incident reports. Yes, there are times that we can’t say what we’d like or what the truth demands but this is a process and if there is going to be any hope of progress this is how it must work.

That, in a microcosm, is the experience of the entire international community with the DRC—how to engage with and coax better governance from a bad government and a failed state. But, all the same, after the next few days I am left wondering whether the people of Rushuru district might be better off without having the army present there.

At this point our convoy is arriving in Rushuru, the district capital, and our destination is the UN base on the far side of town, a military camp surrounded by barbed wire and with guard towers at each corner like a US cavalry fort in the Wild West.

The gate is opened and the convoy vehicles enter the camp, my home for the next 4 days, where I will be hosted by the Indian Army’s 24th Punjab, an infantry regiment that normally does counter insurgency duty in the disputed province of Kashmir. There are 500 soldiers here and a large, professional, and unfailingly proper, officer corps. I will be well taken care of.

Life on an Indian military base when you are a civilian has many of the aspects of summer camp back home in North America. There are neat rows of tents housing officers and men, a bank of shipping containers that serve as offices, and a big marque for the officer’s mess—the camp dining hall. Life is orderly and, yes, regimented. I am led to my quarters, a tent with a camp cot and desk and am met by polished young officers who hand me a schedule of meetings and activities. An army photographer snaps my picture and I am told that I will have drinks with the camp commandant and senior officers before dinner. I am a visiting dignitary.

There is an atmosphere of safety and security here—something made more stark by knowledge of the chaos and rights abuses that exist beyond the wire. From here the 24th Punjab mount round the clock foot patrols and staff a 911 type emergency response centre to dispatch platoons to “the incident reports” that happen at any time. This safety should not be taken for granted—6 months earlier one of the Temporary Operation Bases (TOP) 30km away, and under this command, was breached by rebels and 4 Indian soldiers killed. The incident was investigated intensely and is still talked about by the officers for its lessons on rules of engagement. It also illustrates just how unstable and fluid the area remains.

TOPs are miniature military bases, with about 75 soldiers, surrounded by a barbed wire fence and a single entrance gate with a boom. When a small group of men approached claiming to be surenderees from one of the rebel forces and asking to be processed by the UN—a common occurrence here—the guard on picket duty was distracted while a larger force, covered in banana leaves and armed with juju, rushed the gate and penetrated the camp. Even then the soldiers who emerged from their tents were unsure whether they had the authority for live fire; in the confusion 4 were killed, with steel machetes.

Those responsible turned out to be demobilised members of the Mai Mai militia, now ostensibly part of the government army, but who wished to capture weapons to better resume a life of banditry. Had it ever succeeded in the objective of stealing weapons the Mai Mai would never have found a resupply of ammunition for the Indian Army’s own combat rifles. It was, essentially, a suicide mission and a daft one. The next month the Mai Mai mounted a second attack on another TOP close by but were repulsed with loss of life.

Over the next few days I spent some spare time walking the perimeter of the base, mounting the guard towers and speaking with the sentries. Looking out over the nearby ground, actually a refugee camp for people displaced from the countryside, I considered how long and dull guard duty is almost all the time. It brought to mind a comment from my own Father who served in the Canadian Air Force in Burma in WWII and remarked that military life was composed of long periods of boredom interspersed by moments of unexpected terror.

Over dinner in the mess hall the officers at my table—and the Indian food, served by orderlies who are never far from my side with a fresh chapatti or anything else desired, is very good—are understanding about caution in use of live fire, explaining that they are familiar with difficult operational conditions in Kashmir.

You can be walking through a market on patrol there when the man next to you is shot by a sniper. You can’t fire back or risk harming civilians, which undermines our objectives and can end with you losing your career. This is what we are used to. The rules exist for a reason.

Is Rushuru district now better off than before, during my last visit here 18 months ago? What counts as relatively better is an exercise in parsing and qualification. The southern half of the district, or “the near north” which I have just traversed, and is a day’s drive from Goma, the provincial capital, is secured, but still experiences a high level of human rights violations (HRVs)—usually theft, rape and killings—as well as attacks on and looting of vehicles. Most of these attacks are probably by unpaid government soldiers although the genocidial FDLR are also still active but are under pressure.

Further north from here in northern Rushuru the picture gets worse. The level and frequency of violence is much higher, roads cannot be travelled except in convoys; organised rebel groups, such as the LRA and FLDR are more active and have sanctuaries. There are newer groups emerging also, drawn from factions of the CNDP, a local Tutsi force that has dominated North Kivu militarily for years. Although the CNDP has been amalgamated into the government army under a peace accord, that loyalty is shallow and the struggle for influence and dominance in the army’s North Kivu command between CNDP and “national” officers is one of the under currents of conflict in the area with the ever present prospect that the CNDP could opt out of the army again and plunge the area back into open warfare, something has happened several times in recent years. Already some local commanders have fragmented from it and are on the verge of morphing into something new, another common development in Congo’s fluid conflicts.

Rushuru may not be the worst or most troubled district in North Kivu—there are several contenders for the race to the bottom, Walikale, an Apocalypse Now area immediately to the west of us plagued by guns, mining and money may have that distinction—but it is a troubled place nonetheless. North of Rushuru is Ituri, the next province up, with its own claim to negative excellence among the DRC’s conflict ridden provinces, after which there is Maniema, and then the areas to the west, plus South Kivu province, and so on, each of them their own galaxy of pain.

Is Rushuru, despite its troubles, at least on a path to something better? It may be the belief in hope inherent to the human condition that causes a visitor to the DRC to assume that they are. And yes, in aggregate terms the level of violence may, indeed, be lower than two years ago, just as the DRC in general is not nearly as bad off than it was 5 years ago. But that still leaves an incredible amount of conflict and suffering to pass over in the search for a good trend line. A war or conflict existing at a different level is still a violent conflict.

There were no serious violent incidents in town during the four days I was in Rushuru, though the meeting I sat in on where the Indian officers summarised their previous week of incident reports to a—gorgeous—young French staffer visiting from the UN Human Rights Office, was serious enough: people who were robbed and beaten at gunpoint or shot, women who were raped, vehicles attacked and looted, a bus burned by angry townspeople in front of a government office to protest—unchecked—abuses by the local army detachment.

Climbing into a UN vehicle for the convoy south to Goma the Indian Army officer in charge has a copy of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, strewn over the front seat. Most of the other officers in our group are departing on leave to India and there is an almost festive atmosphere. The officer who is in charge of this convoy and commands a TOP that is last on the line before Goma, 20km north of town, has a serious mien, and tells me he launched mortar attacks against an encroaching FDLR unit in the last week, saying they will be “eliminated” if they try it again.

We don’t know if it’s getting better or not. We are here on 12 month deployment, and are scheduled to move on 6 months from now. All we can do is follow our mandate and hand over to the next detachment that takes over after us.

That detachment may be the last. The government has asked that the UN peace keeping operation leave by the end of the year, not because things are better but because it would rather not have further outside scrutiny and control over is freedom of manoeuvre. What follows probably will not be something better but without the, frequently maligned, UN here to document it, less will probably be heard about it.

Three weeks after I left Rushuru my own organisation, which works with demobilised soldiers and street children in DRC, had its own brush with the violence of this district; our co-director’s brother, working as a driver for the provincial minister of education, was shot and killed in an attack on the minister’s car outside Rushuru town.